CedarDB, the fastest database you’ve never heard of

Disclosure: Amplify is an investor in CedarDB.

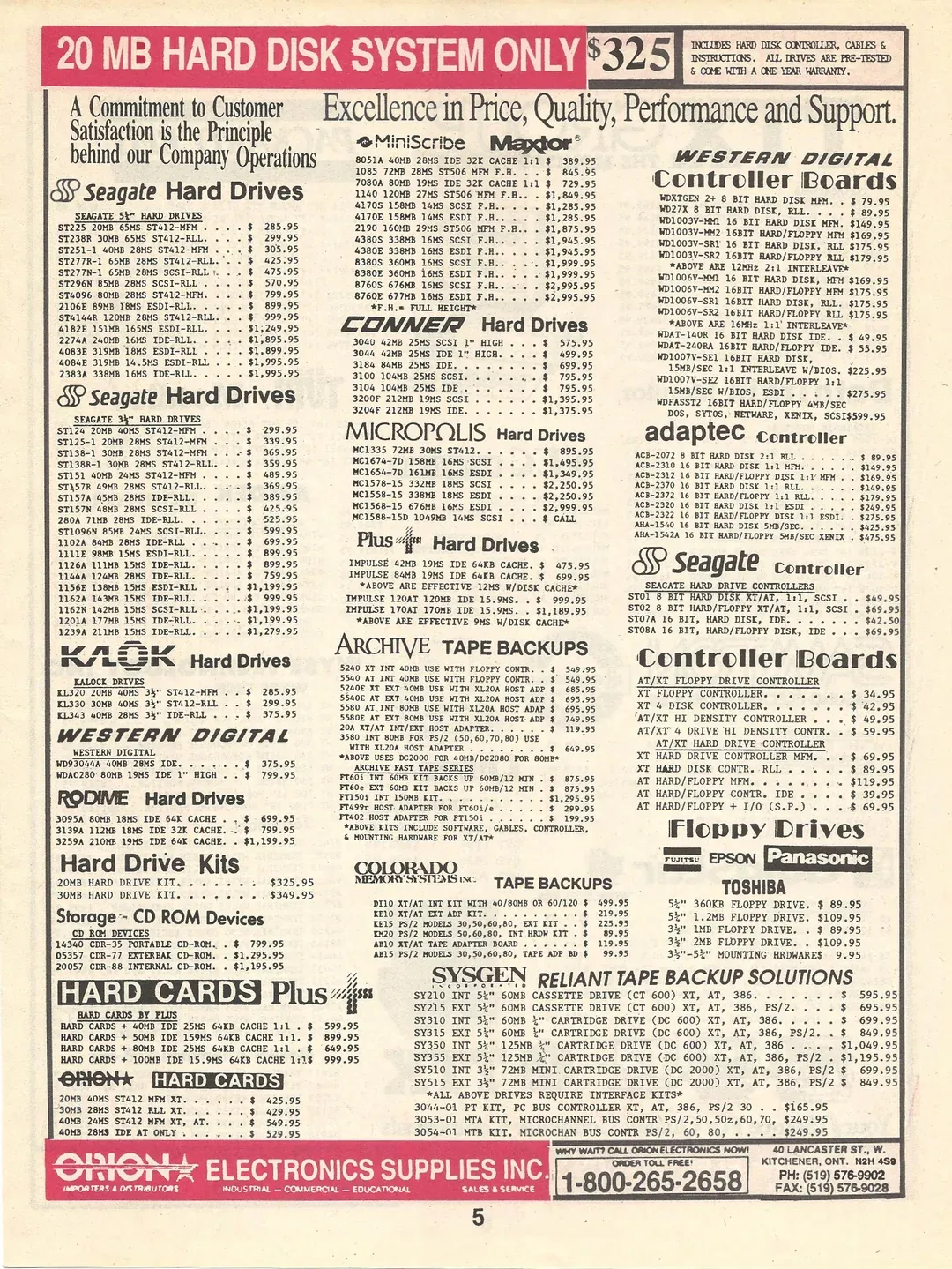

The most popular databases on the planet today — Postgres and MySQL — have (at least) one major thing in common: they were built more than 30 years ago. Things were very, very different back then. Men wore fedoras. Model T cars traversed the New York streets. And as far as computer hardware is concerned, we were living in the dark ages. A 1GB hard drive in 1991 cost thousands of dollars.

While hard drives were already expensive, DRAM capacity was much smaller and prices even higher, so databases of the era were designed around DRAM. Every piece of their architecture was built with RAM constraints in mind. But if you fast forward to today, the hardware world has changed drastically. We now have multicore CPUs with dozens of cores on a single node and terabytes of main memory. But despite this, fundamental characteristics of Postgres and MySQL remain mostly unchanged.

This is far from the first blog post to ask: what would these databases look like if you created them today? What if you could design every piece (and I mean every piece) of a database from scratch to take modern hardware and software into account, from the query planner to the buffer manager? Then you would have CedarDB.

CedarDB started as the Umbra research project at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), where a team of researchers set out to rethink database performance for modern hardware. For the past nine years, they’ve been cooking on every piece of the database stack. And the result, which is now officially in GA, is what many would call the fastest, most capable database in the world.

Based on extensive interviews with their team, this read goes deep on the what and how of the innovations CedarDB brings to the table, including:

- A query optimizer that unnests deeply nested SQL statements

- Code generation for every SQL query

- Morsel-driven parallelism to make full use of all cores

- A modern buffer manager that works in heavily multi-threaded environments

- Architecture that anticipates change, so you can add or change things without breaking stuff

Let’s get into it.

A better query optimizer

The component of a database system that is responsible for finding the best way to execute a query is called the query optimizer. It takes a SQL query and tries to find the most efficient algorithm that can calculate the result.

One of the main ideas behind SQL is that applications tell the database what answer they want and not how to compute it. Thus, it shouldn’t matter how you write your query, since the query optimizer should be able to find the most efficient way to execute it. But most database systems aren’t capable of executing queries efficiently unless you push them (hard) in the right direction. This leads to a lot of manual “helping” of the optimizer, with hints like /*+ USE_INDEX(table, index_name) */ to force specific execution paths, or breaking complex queries into multiple simpler ones and combining the results in application code. (Or, worse, increasing the Snowflake warehouse size to accommodate running an inefficient query.)

These workarounds lead to queries that are effectively optimized for the optimizer, but are harder for humans to read and understand.

Despite the fact that an optimized query can easily outperform a not-so-optimized query by 1000x, not many query optimization improvements have made the leap from research into databases today. And since TUM is one of just a handful of universities that even teaches query optimizer design, its researchers were uniquely qualified to build a better one.

Unnesting nested SQL statements

Systems like SAP and ORMs generate queries with deep nesting structures. Standard query optimizers typically struggle to parse nested SQL statements, often leading to O(n²) runtime complexity that becomes prohibitively expensive for large databases — forcing the hand-tuning described above. CedarDB’s query optimizer can automatically decorrelate any SQL query, so you’re not forced to write simpler SQL statements for the optimizer (which are more time-consuming upfront and harder for you and your teammates to read later).

CedarDB can execute queries that break other systems. A query with deep nesting that takes over 26 minutes on Postgres 16 can execute in just 1.3 seconds after applying the unnesting algorithm developed by Thomas Neumann — an improvement of more than 1000x.

Novel join-ordering algorithms

SQL joins are how the optimizer combines data from multiple tables to serve a query, and the order in which they are applied dramatically impacts query execution. If you’re looking for a 2-bedroom apartment with a roof terrace in SoHo for under $2,000 a month, filtering by budget first is going to get you the quickest result (in this case 0 rows), compared to starting with all rentals in SoHo.

Applying filters in the right order is one way to speed things up, but CedarDB also has some special join algorithms that can perform both joins and aggregation in the same pass, or join multiple inputs at once.

CedarDB’s approach to join ordering is particularly impressive for its ability to handle queries of all sizes. For common queries with fewer than 100 tables, it can find the truly optimal join order. For larger queries — even those joining hundreds or thousands of tables — it uses adaptive optimization that gracefully degrades to near-optimal solutions while maintaining fast optimization times. Where PostgreSQL times out after 700 relations and other systems fail around 100-500 relations, CedarDB’s adaptive framework can handle queries spanning 2 to 5,000 relations.

You can evaluate CedarDB using the Join Order Benchmark if you wish.

A sophisticated statistics subsystem

Since even the best query optimizer is worthless without insights about the data, the statistics subsystem provides estimates to the optimizer beyond what existing database systems support. For example, it can accurately estimate relation size after GROUP BY operations or cardinalities after filtering for distinct values. CedarDB’s statistics can recognize that “Find all Manhattan neighborhoods where the cheapest 2-bedroom apartment costs less than $2,000” – which translates into a MIN aggregation– is impossible to satisfy, which makes a great filter to reduce data early on in the query.

What if your database was actually a compiler?

Most database systems interpret your SQL queries. You write something like:

SELECT

customer_id,

SUM(amount)

FROM orders

WHERE order_date > '2024-01-01'

GROUP BY customer_idAnd the database converts your query into a tree of abstract operations like scanning the orders table, filtering by the date, and so on.

The way most databases use these abstract operations to evaluate SQL queries on user data introduces a lot of overhead. Because the developers of database systems can’t predict every possible query that you, the user{{cedardb-spotlight-fn-1}}, will throw at it, they build a system that can interpret infinite combinations of operators and column types. In a typical query, for each row that’s processed, each operator must:

- Establish what type of data it’s working with

- Check what operation it must perform on the resolved types

- Make function calls to pass data to the next operator

For a query scanning 10 million rows, that’s 10 million catalog lookups, 10 million operation checks…like I said, a lot of overhead. But this didn’t matter particularly much when these databases were built because disk was so incredibly slow anyway. One of the professors at TUM{{cedardb-spotlight-fn-2}} used a metaphor inspired by Jim Gray:

If you have data in memory, you can just go to your basement and fetch the data. But if you have to go to disk, then you have to fly to Pluto. And if you have to fly to Pluto (disk), it doesn’t really matter if you need to walk to your basement a thousand times (reading from main memory 1,000 times) since that is still orders of magnitude faster than flying to Pluto just once.

When most databases were built, disk was incredibly slow and incredibly expensive. Today it is not. Can we build a better interpreter to match this new reality?

A compiler that acts as a database system

CedarDB’s take on this is different: while sharing the same tree of abstract operations as other databases, instead of interpreting the tree for each tuple, they take your query and generate code. For every SQL query that a user writes, CedarDB processes, optimizes it, and generates machine code that the CPU can directly execute — eliminating the interpretation overhead.

If this sounds like a compiler to you, you are right, because this is exactly how Christian Winter (CedarDB co-founder) describes it: “We sometimes say we’re not building a database system, we’re building a compiler that acts as a database system.”

He would know because he was part of the research group that originally developed this new style of query processing at TUM. Although it does introduce some latency (as code must be generated, optimized, and compiled to machine instructions), CedarDB sidesteps this issue by implementing a custom low-level language that is cheap to convert into machine code via a custom assembler.

Now, at this point you’re probably wondering: “Why not just use C++? Why must these researchers reinvent everything? Can we take nothing for granted anymore??”

And you wouldn’t be too far off. Indeed, if Postgres and MySQL are written in C and C++, and CedarDB is written in C++, why not just generate C++ for every query as well? Postgres does actually have JIT compilation for WHERE clauses, so it compiles part of the query, but not all.

The main problem is that the compile times, especially for complex queries, are abysmal. The first version of SingleStore (previously called MemSQL) did this exact approach and would take up to 10 seconds to compile queries on cold starts. Other systems (e.g., Amazon Redshift) rely on heavy query compilation caching to try to hide compilation latencies.

Hyperscalers can deal with minute+ compile times on queries by sharing fragments of compiled query plans across different workloads, but you’re not a hyperscaler.

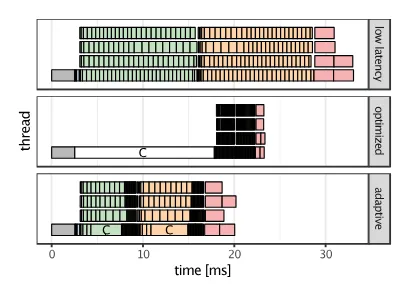

Adaptive Query Execution

Code generation is one approach to improving query execution. Another way that CedarDB improves performance is through Adaptive Query Execution.

The idea here is avoiding overoptimization: CedarDB’s generated code is faster than running traditional queries, but also takes more time up front to compile. If your query doesn’t scan that much data, this is complete overkill. To do so, CedarDB instead starts executing each query immediately with a “quick and dirty” version, while working on better versions in the background.

The upshot is that short-running queries complete quickly without compilation overhead, while more complex long-running queries benefit from optimized machine code.

Always compiling a query to the best possible code upfront (represented by the middle bar labeled ‘C’) has significant overhead. But adaptively compiling the query while it is already running on a faster-to-compile but slower-to-execute code can significantly improve performance, in this example even for queries taking only 20 milliseconds.

A full core workout

At this point CedarDB has generated an optimal plan for your query and converted that plan into specialized machine code. But before we celebrate, there’s another Big Bad Wolf of database latency we have to contend with: work distribution.

Distributing fairly between all available cores is notoriously difficult. Static work assignment is fallible and prone to bottlenecks, analyzing workload size upfront is often inaccurate, CPU utilization doesn’t increase linearly, and using a coordinator process to manage distribution means that cores spend time on coordination instead of working.

So how do most database systems today get around this problem? They essentially all implement varying degrees of parallelism:

- Inter-query parallelism: Each query is executed by its own worker.

- Intra-query parallelism: Each query is processed by multiple workers in parallel, which is important when issuing few but compute-intensive analytical queries.

But even intra-query parallelism quickly runs into Amdahl’s Law: the more cores available, the harder it becomes to keep them all busy. The challenge is data skew and unpredictable work. If you statically divide a query’s 10 million rows into 64 equal chunks (one per core), you can’t predict which chunks will require more processing:

- Core 1 might get a chunk where 99% of rows are filtered out (finishes in 5ms)

- Core 2 might get a chunk of dense data requiring complex computations (finishes in 500ms)

- Cores 1-63 sit idle waiting for Core 2 to finish

The CedarDB team argues that most databases underutilize their hardware. Again, this is no surprise, since many of them were created in a world where “free cores” was more likely to refer to a box of eaten apples than available hardware.

Their clever approach to this problem is called morsel-driven parallelism. Here’s how it works:

- First, CedarDB breaks down queries into segments: pipelines of self-contained operations.

- Then, data is divided into “morsels” per segment – small input data chunks containing roughly ~100K tuples each.

This new abstraction enables much more efficient parallelism than on a per query basis: rather than processing chunks of pre-divided data, whenever a CPU core finishes its current job, it just takes the next chunk from a parallel structure. Like a desk clerk doing data entry of paper forms, it doesn’t matter which stack of forms they grab – only that no clerks process the same forms.

.webp)

For some operations, CedarDB dynamically picks the size of the morsels during runtime. This allows it to generate the ideal size morsels that allow all workers to stay busy, without introducing too much strain on the shared task list.

Since many more morsels wait to be processed than CPU cores exist, CedarDB ensures all cores stay busy until the end, and every query is executed fully parallel from start to end.

Rethinking the buffer manager

Disk was not the only thing that was precious and limited when most databases were developed. Memory was (and still is) too, and because of that many of these databases assume that most data must be loaded from disk (Postgres defaults to just 4 MB of working memory per query!). To safeguard their precious memory, databases have what’s called a buffer manager. It effectively acts as the database club’s bouncer, deciding who’s in or out of main memory.

Yet again, things have changed. Modern systems come equipped with massive amounts of RAM; there’s actually much more “room at the club” than database developers initially assumed. Beyond just capacity, storage itself has diversified: local SSDs, network-attached storage, cloud object stores, and remote memory all have different performance characteristics. There’s more variation in page sizes, and data access patterns range from constant (hot) to once in a blue moon (cold).

Essentially, the job of the bouncer has changed drastically. What should it look like today?

Building a buffer manager for modern systems

The idea of the revamped buffer manager in CedarDB is that you can (and should) expect variance not just in data access patterns, but in storage speed and location, page sizes and data organization, and memory hierarchy.

One of the artificial bottlenecks of traditional database buffer managers is using single-threaded coordination for memory allocation — failing to capitalize on the performance of modern SSDs. To take advantage of performance improvements, a database system needs to access SSDs with multiple threads concurrently, but this leads to a new bottleneck: the buffer manager’s global lock.

CedarDB’s buffer manager is designed from the ground up to work in a heavily multi-threaded environment. It decentralizes buffer management with Pointer Swizzling: Each pointer (memory address) knows whether its data is in memory or on disk, eliminating the global lock that throttles traditional buffer managers. This allows CedarDB to make full use of storage bandwidth even with dozens of threads accessing data simultaneously.

Working sets smaller than RAM capacity run with in-memory speed. CedarDB’s query performance is primarily constrained by RAM bandwidth, which typically operates around 100 GB per second. Should the working set exceed RAM, CedarDB’s sophisticated buffer manager starts reading data from and writing it to background storage while ensuring that the performance degrades gracefully.

The idea is that if your data fits in main memory, it should be as fast as an in-memory database. But if you don’t have enough main memory, it should then max out usage of your fast SSDs (if you have them) to get the best possible performance before gracefully slowing down.

CedarDB is effectively a “beyond main memory” system—memory is your primary target, but it scales beyond what you have in memory.

Things are going to change again

One feature of Postgres and MySQL is that they’re very slow to change. The fundamentals don’t shift much over time. I chose the word “feature” carefully because this intransigence isn’t some unfortunate consequence, it’s literally part of the design{{cedardb-spotlight-fn-3}}. It’s exactly this stability that gives each generation the confidence to build their apps (no matter how different they are) on systems like Postgres. You know what you’re getting. The rug will not be pulled out from under you, and there will not be breaking changes.

But as we’ve seen, there is also a clear downside to this rigidity. The hardware world has changed so profoundly, and yet so many aspects of databases simply cannot be totally redone. And this change is coming from all directions; who knows where things will be in 10 years, and what we’ll wish our databases could do then.

For an example of this diversity of change, take network-attached storage (NAS): you can now get 400 gigabits of throughput to Amazon’s S3 object storage, which is faster than your local storage. Remote memory via CXL ( the current favorite for the next revolution of resource allocation) is another development the databases of the past couldn’t have anticipated. The database of the future needs to assume things will change and build that change into the fundamentals of the system, and this is exactly how CedarDB designed their storage architecture.

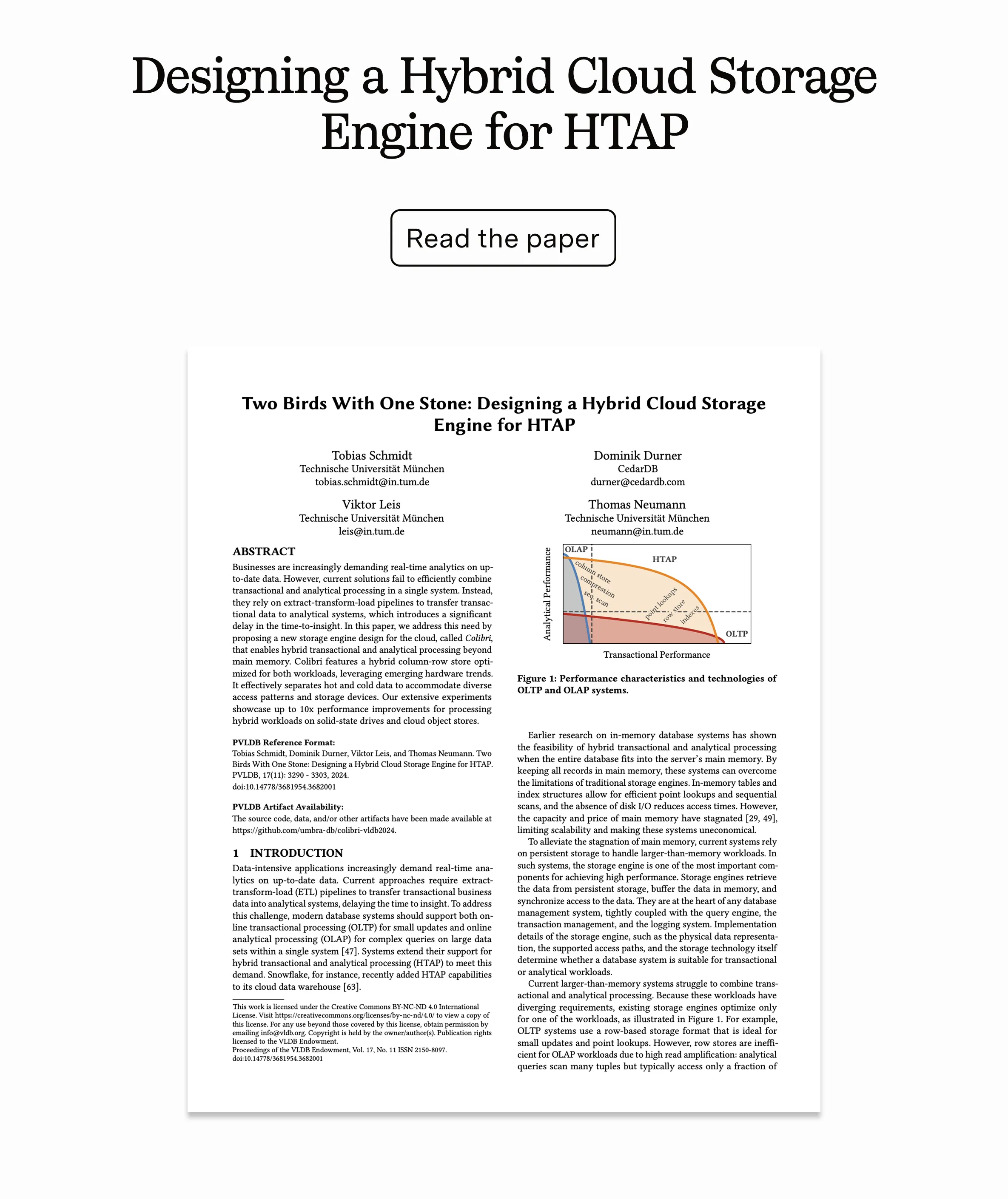

The most popular databases tend to optimize for one type of workload, which then also dictates the types of hardware and technologies a system uses: different types of physical storage (SSD, cloud, network-attached storage), storage models (row based, column based, or access patterns (hot, warm, cold).

CedarDB’s storage class system employs pluggable interfaces where adding new storage types doesn’t require rewriting other components. The buffer manager treats each class as an endpoint with defined characteristics, but the query engine, optimizer, and other components don’t need to know the specifics. FWIW, a few enterprise DBs like Microsoft SQLOS support this idea as well.

If CXL becomes the go-to storage interface at some point in the future, you don’t need to write another whole component, you just need another endpoint for the buffer manager. The same with supporting new workloads: Moritz Sichert, CedarDB co-founder and CEO, was able to build a vector type for vector databases over a weekend because the interfaces were designed so that plugging in new operators and modes is expected and easy.

~

The database landscape has been dominated by systems built for a radically different hardware reality, while the innovation that’s badly needed typically languishes in research papers without ever making it into real-world applications. At TUM, the long-running Umbra project made the perfect sandbox for trialling new developments, on a timeline rarely afforded to either database companies or individual researchers. CedarDB is the product of this environment, helping database research advancements make the leap into an actual database system that you can try out for free today.